Atrial Tachycardia

Atrial tachycardia is the least common type of supraventricular tachycardia. It's generally seen in children with underlying heart disorders such as congenital heart disease, particularly those who've had heart surgery.Atrial tachycardia may also be triggered by factors such as an infection or drug or alcohol use. For some people, atrial tachycardia increases during pregnancy or exercise.

Atrial tachycardia is a form of supraventricular tachycardia that occurs when one focus in the atria begins to fire rapidly, overwhelming the sinoatrial node. This results in rapid conduction of action potentials through the atrioventricular node, causing elevated ventricular rates. The atrial rate during atrial tachycardia is usually between 100 and 200 beats per minute. A narrow complex tachycardia results with P wave morphologies that are different than normal sinus P waves. The QRS complex can be wide if aberrancy is present (ie, right or left bundle branch blocks).

Symptoms of atrial tachycardia depend on the ventricular rate and the duration of the tachycardia. The symptoms include palpitations from the rapid heart rate. If hypotension ensues, dizziness and weakness can occur. The shortened diastolic filling time during tachycardic states can lead to decreased cardiac output and symptoms of congestive heart failure.

Atrial tachycardia is best treated with AV blocking medications, such as beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. Adenosine can, at times, terminate the rhythm, but not always. Ablation of atrial tachycardia is also an option, especially when medical therapy fails.

Special Situations:

Atrial tachycardia with 2:1 block; when atrial tachycardia occurs with a 2:1 conduction block, digoxin toxicity should be considered.

Atrial Tachycardia with 2:1 conduction

Pathophysiology

Several pathophysiologic mechanisms have been ascribed to atrial tachycardia. These mechanisms can be differentiated on the basis of the pattern of onset and termination and the response to drugs and atrial pacing.

Enhanced automaticity

Automatic atrial tachycardia arises due to enhanced tissue automaticity and is observed in patients with structurally normal hearts and in those with organic heart disease. The tachycardia typically exhibits a warm-up phenomenon, during which the atrial rate gradually accelerates after its initiation and slows prior to its termination.

Automatic atrial tachycardia is rarely initiated or terminated by a single atrial stimulation or rapid atrial pacing, but it may be transiently suppressed by overdrive pacing. It almost always requires isoproterenol infusion to facilitate induction and is predictably terminated by propranolol. [10] Carotid sinus massage and adenosine do not terminate the tachycardia even if they produce a transient AV nodal block. Electrical cardioversion is ineffective (being equivalent to attempting electrical cardioversion in a sinus tachycardia).

Triggered activity

Triggered activity is due to delayed after-depolarizations, which are low-amplitude oscillations occurring at the end of the action potential. These oscillations are triggered by the preceding action potential and are the result of calcium ion influxes into the myocardium. If these oscillations are of sufficient amplitude to reach the threshold potential, depolarization occurs again and a spontaneous action potential is generated.

If single, this is recognized as an atrial ectopic beat (an extra or premature beat). If it recurs and spontaneous depolarization continues, a sustained tachycardia may result.

Most commonly, atrial tachycardia due to triggered activity occurs in patients with digitalis intoxication . or conditions associated with excess catecholamines. Characteristically, the arrhythmia can be initiated, accelerated, and terminated by rapid atrial pacing. It may be sensitive to physiologic maneuvers and drugs such as adenosine, verapamil, and beta-blockers, all of which can terminate the tachycardia.

Occasionally, this atrial tachycardia may arise from multiple sites in the atria, producing a multifocal or multiform atrial tachycardia. This may be recognized by varying P wave morphology and irregularity in the atrial rhythm.

Pulmonary vein tachycardias

Pulmonary vein tachycardias originate from the os of the pulmonary vein or even deeper localized atrial fibers. These strands of atrial tissue are generally believed to gain electrical independence, since they are partially isolated from the atrial myocardium. These tachycardias are typically very rapid (heart rate of 200-220 bpm or more)

Although pulmonary vein tachycardias frequently trigger episodes of atrial fibrillation, the associated atrial tachycardias may be the clinically dominant or exclusive manifestation. The latter typically involves only a single pulmonary vein as opposed to the multiple pulmonary vein involvement seen in atrial fibrillation.

Reentrant tachycardia

Intra-atrial reentry tachycardias may have either a macroreentrant or a microreentrant circuit. Macroreentry is the usual mechanism in atrial flutter and in scar- and incision-related (postsurgical) atrial tachycardia.

The more common and recognized form of atrial tachycardia, seen as a result of the advent of pulmonary vein isolation and linear ablation procedures, is left atrial tachycardia. In this situation, gaps in the ablation lines allow for slow conduction, providing the requisite anatomic substrate for reentry. These tachycardias may be self-limiting but if they persist, mapping and a repeat ablative procedure should be considered.

Microreentry can arise in a small focal area, such as in sinus node reentrant tachycardia. Typically, episodes of reentrant atrial tachycardia arise suddenly, terminate suddenly, and are paroxysmal. Carotid sinus massage and adenosine are ineffective in terminating macroreentrant tachycardias, even if they produce a transient AV nodal block. During electrophysiologic study, it can be induced and terminated by programmed extrastimulation. As is typical of other reentry tachycardias, electrical cardioversion terminates this type of atrial tachycardia.

Classification of atrial tachycardia

Based on endocardial activation, atrial tachycardia may be divided into 2 groups: focal and reentrant. Focal atrial tachycardia arises from a localized area in the atria such as the crista terminalis, pulmonary veins, ostium of the coronary sinus, or intra-atrial septum. If it originates from the pulmonary veins, it may trigger atrial fibrillation and often forms a continuum of arrhythmias.

Reentrant (usually macroreentrant) atrial tachycardias most commonly occur in persons with structural heart disease or complex congenital heart disease, particularly after surgery involving incisions or scarring in the atria. Electrophysiologically, these atrial tachycardias are similar to atrial flutters, typical or atypical. Often, the distinction is semantic, typically based on arbitrary cutoffs of atrial rate.

Some tachycardias cannot be easily classified. Reentrant sinoatrial tachycardia (or sinus node reentry) is a subset of focal atrial tachycardia due to reentry arising within the sinus node situated at the superior aspect of the crista terminalis. The P wave morphology and atrial activation sequence are identical or very similar to those of sinus tachycardia.

Diagnostic Considerations

The differential diagnosis of atrial tachycardia is the differential diagnosis of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and includes the following:

- Sinus tachycardia

- Atrial flutter (see the image below)

- Atrial fibrillation

- Atrioventricular (AV) junction–dependent reentrant tachycardias (AV nodal reentrant tachycardia and AV reentrant tachycardia using an accessory pathway)

Differentiating among these diagnoses requires electrocardiographic (ECG) analysis of the tachycardia for P wave activity. In SVT, the ECG typically has narrow QRS complexes (unless aberrant conduction with typical left or right bundle-branch block occurs or a bystander preexcitation is seen).

Assessment of the relationship of the P waves to the QRS complex (R waves) can help to guide diagnosis. A short RP interval (P wave immediately following the QRS) suggests different causes of the tachycardia than does a long RP interval (interval wave preceding QRS).

In short RP interval SVT, the differential diagnosis includes the following:

- Typical AV nodal reentrant tachycardia

- AV reentrant tachycardia using accessory pathways

- Atrial tachycardia with long first-degree AV block

- Atrial tachycardia originating from the os of the coronary sinus or junctional tachycardia

To determine the diagnosis requires additional maneuvers, such as vagal stimulation (eg, carotid sinus massage, Valsalva maneuver), or adenosine.

In long RP interval SVT, the differential diagnosis includes the following:

- Atypical (fast-slow) AV nodal reentrant tachycardia

- Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia (PJRT) due to a slowly conducting retrograde accessory pathway

- Atrial tachycardia

- Sinus tachycardia

- Sinus node reentry

- Atrial flutter

- AV reentrant tachycardia

Diagnosis requires assessment of the patient condition, vagal maneuvers, adenosine, and cardioversion—namely, procedures that may not only be diagnostic but also therapeutic.

For multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT), the differential diagnosis includes atrial fibrillation because both can manifest with an irregular pulse. MAT with aberration or preexisting bundle branch block may be misinterpreted as ventricular tachycardia (VT).

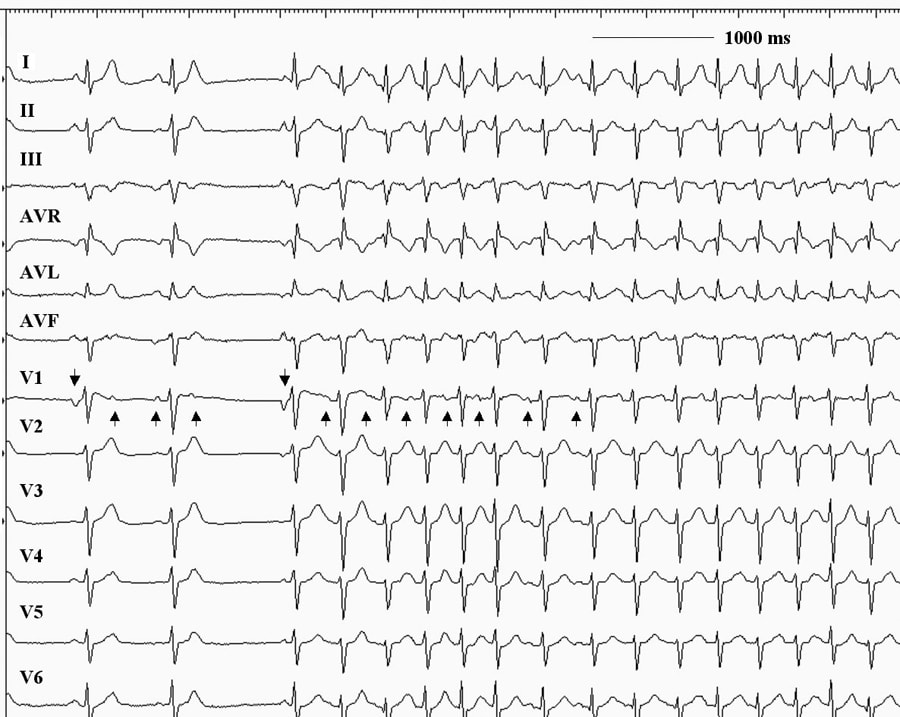

This 12-lead electrocardiogram demonstrates an atrial tachycardia at a rate of approximately 150 beats per minute. Note that the negative P waves in leads III and aVF (upright arrows) are different from the sinus beats (downward arrows). The RP interval exceeds the PR interval during the tachycardia. Note also that the tachycardia persists despite the atrioventricular block.

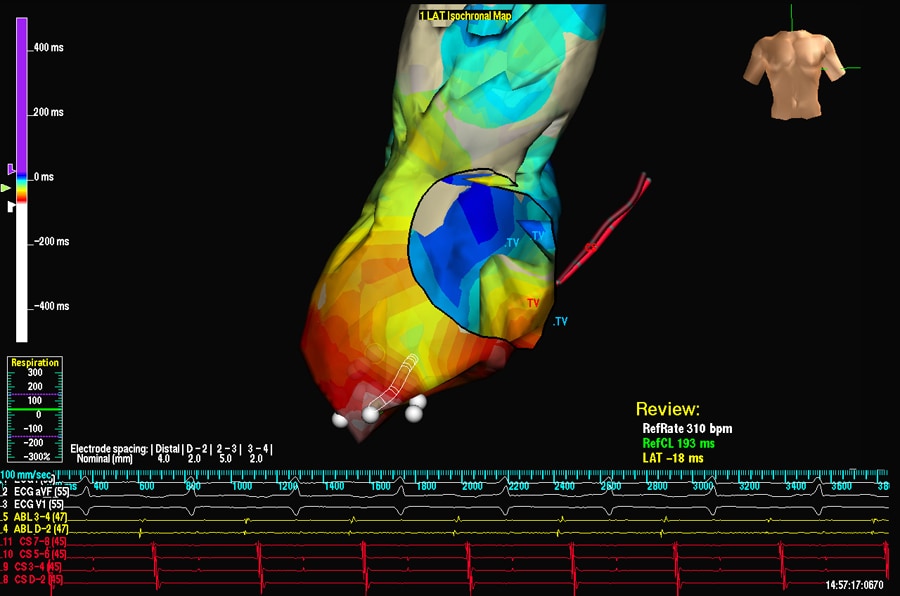

Anterior-posterior projection is shown. An example of activation mapping using contact technique and EnSite system. The atrial anatomy is partially reconstructed. Early activation points are marked with white/red color. The activation waveform spreads from the inferior/lateral aspect of the atrium through the entire chamber. White points indicate successful ablation sites that terminated the tachycardia. CS = shadow of the catheter inserted in the coronary sinus; TV = tricuspid valve.

Diagnosis

Tests and procedures used to diagnose atrial tachycardia may include:- Blood tests to check thyroid function, heart disease or other conditions that may trigger atrial tachycardia

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) to measure the electrical activity of your heart and measure the timing and duration of each heartbeat

- Holter monitor, which is a portable ECG device designed to record your heart's activity as you go about your routine

- Echocardiogram, which uses sound waves to produce images of your heart's size, structure and motion

- Stress test, which is typically done on a treadmill or stationary bicycle while your heart activity is monitored

- Electrophysiological testing and mapping, which allows your doctor to see the precise location of the arrhythmia

Treatment

Treatment of atrial tachycardia depends on the severity of the condition and the factors that trigger it. In addition to managing any underlying conditions that could trigger your atrial tachycardia, your doctor may recommend or try:- Vagal maneuvers. You may be able to temporarily slow your heart rate by using particular maneuvers that include holding your breath and straining, dunking your face in ice water, or coughing.

- Medications. Your doctor may suggest intravenous or oral medication to control your heart rate or restore a normal heart rhythm.

- Cardioversion. If your arrhythmia (irregular heart beat) does not respond to vagal maneuvers or medication — and if there's no identifiable, treatable condition triggering it to occur — your doctor may use electrical cardioversion. In the procedure, a shock is delivered to your heart through paddles or patches on your chest. The current affects the electrical impulses in your heart and can restore a normal rhythm.

- Catheter ablation. In some cases, your doctor may recommend catheter ablation. For this procedure, your doctor threads one or more catheters through your blood vessels to your heart. Electrodes at the catheter tips can use heat, extreme cold or radiofrequency energy to damage (ablate) a small spot of heart tissue and create an electrical block along the pathway that's causing your arrhythmia.

- Pacemaker. If you experience frequent episodes of atrial tachycardia and all other treatment options are unsuccessful, your doctor may suggest implanting a small device called a pacemaker to emit electrical impulses that stimulate your heart to beat at a normal rate. For people with atrial tachycardia, this procedure is typically followed by an ablation of the AV node.

No comments:

Post a Comment